Oct. 28, 2025 marks the tenth anniversary of the last time an Avro Vulcan took to the skies. Following eight years of renewed airworthiness, XH558 landed on Oct. 28, 2015 after one final display.

In circumstances that remain hotly discussed even a decade later, it was announced by the Vulcan to the Sky Trust (VTST) in May 2015 that that summer’s display season would be the last where crowds could see their Cold War-era strategic bomber, the Avro Vulcan, in the skies.

Critical industry partners like BAE Systems and Rolls-Royce, on whose support the Vulcan’s permit to fly from the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) was based, had told VTST that due to dwindling expertise on the aircraft and the increasing hours on the ageing airframe their status as technical authorities would be rescinded at the end of the 2015 season.

Their aircraft, serial number XH558 (also known under the civilian registration G-VLCN), had been performing to airshow crowds since 2008 following an extensive effort to return the aircraft to flight for the first time since 1993. The fundraising campaign began in 1999, and with the help of public donations and Heritage Lottery funding the aircraft began test flights in October 2007. Approximately £6.5 million had been raised by VTST by this point.

XH558 was initially retired from the Royal Air Force in 1984, two years after the type’s combat debut over the Falkland Islands. The following year, the airframe was reactivated to serve in the Royal Air Force’s Vulcan Display Flight (VDF) and replace airframe XL426. XH558 continued with the VDF, eventually as the sole airworthy Vulcan, until the unit was disbanded after the 1992 display season. Increasingly restricted budgets following the end of the Cold War forced the RAF to streamline its inventory and operations, seeing not only the end of the VDF but also the withdrawal of the F-4 Phantom II, Blackburn Buccaneer, and fellow V-Bomber the Handley Page Victor from service.

Sold to private owners, the aircraft became part of the collection at Bruntingthorpe. Its landing there on Mar. 23, 1993 would be its last for 15 years, though it was maintained in a taxiable condition until plans, led by Dr Robert Pleming, came together for the return to flight.

The Vulcan and the V-Bombers

Entering service in 1956, the Avro Vulcan was one of four jet-powered strategic bomber designs commissioned by the Royal Air Force in the late 1940s in order to replace piston-engined bombers which were rapidly becoming obsolete. Of the four designs that matured into flying examples – the Avro Vulcan, the Handley Page Victor, the Vickers Valiant, and the Short Sperrin, three were selected to enter service. The Vulcan, Victor, and Valiant would together come to be known as the V-Bomber force. The Sperrin, though never passing the prototype stage, served its purpose well as a fall-back or interim option should the development of the V-Bombers stall.

Procured together to guarantee the viability of Britain’s nuclear deterrent should an issue be discovered with any of the designs, the Vulcan and Victor represented the most progressive, advanced concepts, while the Valiant was an arguably more conservative design. The Valiant, though, as a consequence of being the first to enter service, does hold the distinction of being the aircraft tasked with dropping the UK’s nuclear and thermonuclear weapons in live test sorties.

The Vulcan featured what was, at the time, a groundbreaking delta-wing design. Initially with a straight leading edge and cropped wingtips – leading to the nickname ‘tin triangle’ – the wing design was refined for improved aerodynamics with a slight kink around the midpoint. By the time of the Vulcan B2 variant, of which XH558 is one, the shape had been refined even further to create a smoother, almost curved leading edge that we are familiar with.

All three V-Bombers served on alert status ready to deliver their nuclear payloads to targets in the Soviet Union in the early days of the Cold War. The threat from surface to air missiles soon became apparent, not least following the shootdown of Gary Powers’ U-2 spy plane in 1960. Rather than the high altitude level bombing they’d been designed for, the V-Bombers would have to switch to low level tactics to secure their place in the RAF’s inventory. Of the three designs, the Vulcan, with some wing strengthening, proved the most suitable for this adapted role. It was also noted, due to the Vulcan’s shape, that the aircraft had a smaller radar cross-section that would be expected for an aircraft of its size.

The Victor, impressive in its own right as the fastest of the three – with the largest payload – found form as a refueling tanker and in the strategic reconnaissance role. Eight Victors served in the 1991 Gulf War, providing fuel to RAF Tornados as they launched strikes against Iraqi targets. The Valiant, despite its early time in the spotlight and conversion to other roles, ended up suffering from major fatigue cracks and corrosion in the wing spars. Though they remained on nuclear QRA into the early days of 1965, the last RAF Valiant sortie was flown in December 1964.

RAF Bomber Command was closely linked with its U.S. counterpart, and its V-Bombers were able to be directed by the Supreme Allied Commander Europe, a NATO post that has always been held by an American – though the final decision to deploy UK nuclear forces would’ve always rested with the Prime Minister. During the Cuban Missile Crisis, V-Bomber units were placed on high alert ready to take-off with their nuclear payloads at a few minutes’ notice. Though their U.S. equivalents carried out dispersal plans and increased their airborne alert force, the order to disperse V-Bombers to designated airbases across the country was held back by Downing Street where Prime Minister Macmillan favored caution.

Vulcans continued to sit on nuclear alert at varying readiness levels until 1970, when the Royal Navy declared its first ballistic missile submarines ready for service. The submarines carried the Polaris missile, which had been bought by the UK under the Nassau Agreement in place of the cancelled GAM-87 Skybolt air-launched ballistic missile. The Avro Blue Steel nuclear-armed cruise missile which had been the most survivable, and therefore arguably most potent, weapon available to the V-Bomber force since 1963 was withdrawn at the same time. Any future nuclear weapons delivered by the RAF’s strategic bombers would have been unguided WE.177 gravity bombs.

After standing down from high readiness alert, the Vulcan force led a mostly quiet life. By the early 1980s, the fleet was in its twilight days, and those operating the aircraft enjoyed comfortable days of training missions and occasional overseas deployments to desirable locations like Nevada, USA. This all changed rapidly in 1982 when the increasingly decrepit airframes were fixed up as best they could be, and the effectively mothballed refueling capability reinstated, to allow the Royal Air Force to play a direct part in the Falklands War ahead of the arrival of the Royal Navy’s task force.

Flying from Ascension Island using daisy-chained Victor tankers, the missions pushed the very limits of these jets’ endurance. Seven missions, codenamed Operation Black Buck 1 through 7, were launched, with five successfully delivering an attack. Initially, these focused on cratering the runway at Port Stanley in an attempt to cripple the Argentinian forces’ ability to resupply or station fast jets on the islands. Later, AGM-45 Shrike anti-radiation missiles were carried and launched in unsuccessful attempts to destroy a AN/TPS-43 radar unit that had been set up near the airfield.

Black Buck gave the operational Vulcan fleet a short reprieve. The duration of their bombing runs was only eventually surpassed by B-2 Spirit stealth bombers of the U.S. Air Force, though the fraughtness of Black Buck with its elderly aircraft and complex refueling plan certainly pushed human endurance much further.

The Avro Vulcan was finally retired from frontline service in March 1984, having served the Royal Air Force for 28 years.

Highs and Lows

Though hugely popular with airshow crowds, taking centre stage in commemorations of the Falklands War and making a number of flypasts alongside the RAF’s Red Arrows display team, XH558’s civilian display career was always difficult to sustain. Reserves of money and mechanical spares were continual issues – hundreds of thousands of pounds were spent per year on fuel alone, with the jet needing 2,500 litres to complete each display.

In October 2012, VTST announced that the following 2013 season was planned to be XH558’s last. Even then, three years before its final flight, XH558 had flown more hours than any other Vulcan ever had. To carry on flying after 2013, a major reinforcement of the aircraft’s wing structure was necessary. Mid-season, 2013, the decision was taken to potentially extend the aircraft’s career by seeking funds to carry out the work. This campaign, labelled Operation 2015, reached its goal towards the end of the year just before the Vulcan headed in for its winter service period. The modification was successful, guaranteeing two more years on the display circuit.

2014 saw an extraordinary opportunity to honor the Vulcan’s historical lineage as a design emanating from the sketches of Avro’s Roy Chadwick. Chadwick, who tragically was killed in an aircraft crash before he could see the Vulcan take its final shape, had proven his skills as a designer with the Avro Lancaster, Avro Lincoln, Avro York, and Avro Shackleton. Visiting the UK for six weeks of this year was the Avro Lancaster ‘Vera’, operated by the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum.

#ThrowbackThursday #Avro sisters – by John Dibbs in 2014

The 2014 display season saw the visit of @CWHM ’s Lancaster, ‘VeRA’. She joined @RAFBBMF ‘s Lancaster PA474, and Vulcan #XH558 for the historic moment of seeing these classic Avro sisters together. pic.twitter.com/uOgUKjIkUG

— Vulcan XH558 (@vulcantothesky) August 22, 2019

Touring the country with the only other airworthy Lancaster in the world, the one belonging to the RAF’s Battle of Britain Memorial Flight, the formation of two Lancasters was a breathtaking sight on its own. XH558’s brief life extension made it possible for Avro’s next generation bomber to join the formation too, and add to the sound of eight Rolls-Royce Merlin piston engines with its four Rolls-Royce Olympus turbojets.

Dark Day

At the height of what would indeed turn out to be XH558’s final season, the jet was set to fly at no fewer than three airshows on a single day. Aug. 22, 2015 was the day of what would turn out to be the last ever Dawlish Air Show, the second day of the Bournemouth Air Festival, and the first day of the Shoreham Airshow.

Shortly before XH558’s display slot at Shoreham, a performance by a Hawker Hunter T7 ended in tragedy when the aircraft failed to complete a loop and crashed into the nearby A27 road. Eleven people were killed, though the pilot – Andy Hill – survived with critical injuries. His role in the crash would go on to make headline news for years to come, and in May 2025 his final appeal for the reinstatement of his pilot license was rejected.

Arriving overhead shortly after G-CVIX, a De Havilland Sea Vixen, had performed a respectful flypast, XH558 rolled in to do the same. Display flying had, understandably, been cancelled. Instead, the crowd fell silent as XH558 performed a single flypast at 1,000 feet. As it departed, the crew dipped the aircraft’s wing over the Hunter’s crash site as a mark of respect.

Despite the disaster at Shoreham, the news of which was now trickling to aviation enthusiasts across the country, the Vulcan pressed ahead with its final display of the day at Dawlish – aware that many had gathered specifically to see XH558 one last time. The atmosphere on the popular viewing area Smugglers’ Hill – where the author was stood – that day rapidly took a turn as phones were checked and word spread around. Questions were raised as to whether the Dawlish show would continue that day – in the event, it did, though the tail end was disrupted by changing weather.

The thing people who were at Dawlish that day probably remember the most from the air display was XH558’s entrance. Flying along the dramatic coastline, the aircraft let out an enormous howl – the signature of Olympus 201-equipped Vulcans when they’re throttled to around 90%.

One can only imagine the emotions felt in the cockpit during this display, which – despite the deteriorating weather – was well received by all. For the crew to have seen first-hand the devastation at Shoreham, to then proceed with their air display at Dawlish as usual, surely took guts.

Rules rapidly enacted post-Shoreham restricted overland displays by historic jets across the UK, initially scuppering XH558’s final few displays. Soon after, following negotiation with the CAA, it was announced that the Vulcan was permitted to continue its ‘non-aerobatic’ display with a few tweaks. Final airshow appearances were completed in early October before XH558 set off on a two-day tour of flypasts over sites associated with the V-Bomber force across Britain on Oct. 10 and Oct. 11.

The Finale

Under a veil of secrecy, intended to prevent amassed crowds causing the flight’s cancellation (with the Shoreham disaster fresh in everyone’s minds), XH558 took off from its Doncaster Sheffield Airport (formerly RAF Finningley) home on Oct. 28, 2015. Among its five crew members was Martin Withers, who had been one of XH558’s display pilots and most notably was the lead pilot of the mission airframe during the first Black Buck mission.

Just after 2pm, the jet began its roll out to the runway. 15 minutes of flight later and it was all over. XH558 was taxied back to the hangar under a water cannon salute. Its days in the sky were done.

On 28 October 2015, over 55 years after her first flight, Avro Vulcan XH558 flew for the final time.

Wing Commander Bill Ramsey, the last captain of Vulcan XH558, relives the final flight and narrates his thoughts from that day.https://t.co/I46GJU2jLp pic.twitter.com/GmPNHBtv7M

— Vulcan XH558 (@vulcantothesky) October 28, 2022

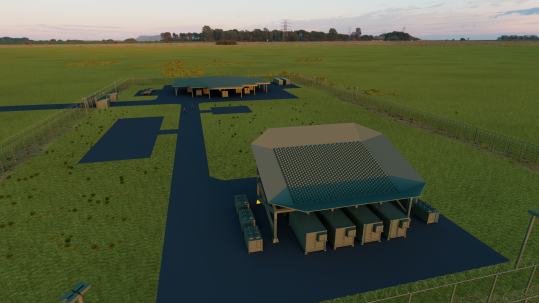

The decision to retire XH558 to Doncaster Sheffield Airport remains controversial. Plans to develop the aircraft into a visitors’ attraction with high speed taxi runs and a bespoke hangar have faltered. No longer the owner of the world’s last airworthy Vulcan, but one of several taxiable Vulcans in the UK, VTST hit major financial struggles. After being forced to leave their hangar in 2017, VTST were regrettably forced to leave XH558 outside and exposed to the elements for a significant period of time.

To complicate matters further, Doncaster Sheffield Airport was closed by its owners in 2022 and remains so to this day. Plans are afoot to re-establish the airfield, hopefully with a view to include the Vulcan as part of its regeneration, but the final details are still under discussion.

A stimulating visit on Friday to @vulcantothesky to view #XH558 and discuss potential options for the future. @MyDoncaster @MayorRos @SouthYorksMayor @NickFletcherMP pic.twitter.com/bfnBsCeowT

— Damian Allen (@DoncasterDamian) March 13, 2022

An alternative option, much floated at the time of its final retirement, to send XH558 back home to Bruntingthorpe would have also, unfortunately, failed in the long term. A massive downsizing of the aviation business at the site saw the end to the famous fast taxi events featuring Victors, VC-10s, Lightnings, and more. Some aircraft were scrapped, others only partially preserved. It is impossible to know exactly what fate would have fell upon XH558, but in retrospect it’s unlikely to have beaten the jet’s current situation.

XH558’s tale will forever be controversial. Proponents point to the enthusiasm the jet generated for aviation in the UK, the ability for a whole new generation to see a British aviation icon just years after the last flights of Concorde. Those with more skeptical views will point towards the money spent and wonder just how many other less complex historic aircraft could have been restored to flight for the same – arguing also that the Vulcan’s time in the spotlight adversely affected awareness of other aircraft with important histories. Neither perspective is incorrect.